Several years ago, I sat down to watch a documentary on African spirituality. I’ve always been interested in religion and culture, and was curious to learn more about indigenous African traditions. As I watched, I thought about whether or not I could have been distantly related to the people I saw on television. I wondered what my life would have been like, had my ancestors not been taken from the shores of Africa and brought to the United States. Would I be here? Would I practice one of these indigenous spiritual traditions? The practices I was seeing on television seemed so foreign to my everyday reality. But then, the documentary began to cover a ceremony in which a designated person became “posessed” by the spirit of whatever god they wanted to communicate with. And once the person was fully posessed by this spirit, he or she began to dance. I was instantly stuck by the familiarity of the dancing. I’d never been to Africa, nor had I any experience with the particular tribe or faith being featured on the documentary. But I knew that dance. I had seen it countless times.

Growing up in a predominantly Black church, I regularly witnessed church members “catch the Holy Ghost.” Often, this played out in the form of dance. Men and women would dance in such a way that it seemed their bodies had been taken over – or possessed – by the Spirit. I was filled with awe at how far into the future and how far across the world these bodily movements had traveled. When Africans brought to American shores were banned from practicing their indigenous faiths, they simply infused some of these familiar practices into their new faith. And today, “catching the Holy Ghost” is a staple of the Black church experience.

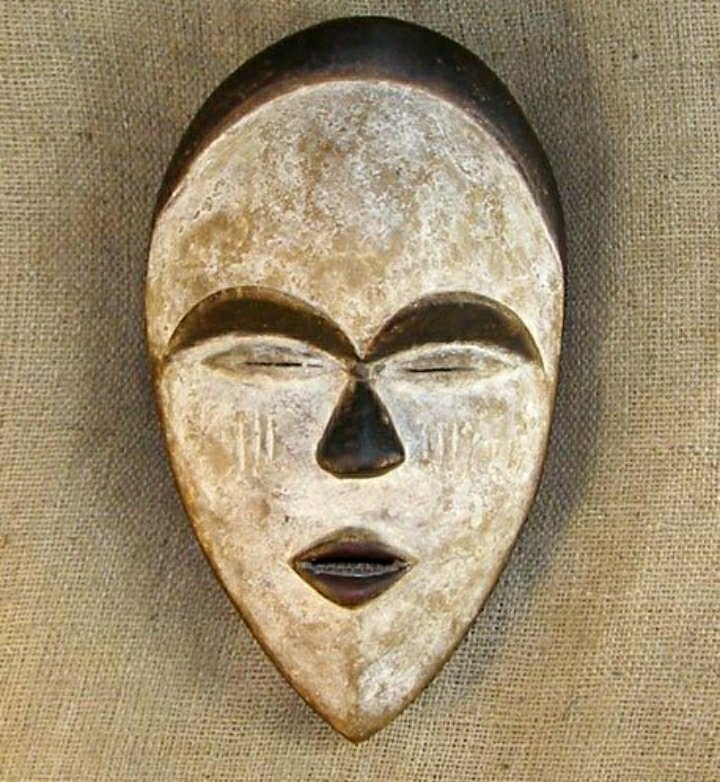

But Black people in diaspora are leaving their churches en masse, and turning back toward the spiritual systems of our ancestors. In the effort to “decolonize our minds,” many of us have taken steps to reconnect with Africa. Sometimes, this comes in the form of DNA tests that reveal ethnic origins. Other times, this means investing in Africa and buying Black when outside of Africa. Sometimes, this means taking an African name, wearing African clothing, or learning to make African foods. And in many cases, this means learning about and transitioning into the spiritual traditions of one’s ancestors. And because we live in an age where we can reconnect with our stolen identities in ways that were never possible before, we are wasting no time in reclaiming ourselves.

I have to admit that over the years I have felt heavily torn by this movement toward African spirituality. As a child growing up in a diverse area, I have always loved learning about culture. I often felt the sting of being the only one who wasn’t able to point to a place in the world and say that it was where my family came from. I knew early on that my place in America was not a place of belonging, but a displacement of sorts. I’d been born here. But this is not a place where I ever felt at home. And within Christianity, things were about the same. As I grew older, I wanted the ability to define myself as a Black woman, as a descendant of Africa. I wanted to stop being held under the weight of European standards. European standards of beauty, of intelligence, of goodness, of propriety, of spiritual maturation. I wanted to stop striving for the approval of White people – which I thought would help me to have a successful life – and just be myself. But it’s more than just connecting with my African roots. Before I knew that they were African beliefs, I believed things that are inherently African. I believed in the existence of my ancestors. I believed that nature is infused with spirit. And I have always been able to see the divine interconnectedness of all life.

When Christianity came to West Africa, it was used to oppress. Those with indigenous beliefs, held from the beginning of time, were seen as no more than inferior savages needing to be ‘civilized,’ yet incapable of fully becoming so. Their systems of spirituality were crushed.,their history disrupted, and their stories forgotten. The Christian witness of love was traded for wealth. And in order to do this, African life had to be demonized and dehumanized. Why is it that we can look at Greek, Norse, or Celtic mythology with interest and appreciation – but we view African mythology as mysterious at best (Egyptian mythology) and demonic at worst (Yoruba Orishas)? And over time, as our self-hatred was internalized, Black people used Christianity to demonize, abuse, and oppress each other.

I know that Jesus Christ, himself, is not the oppressor. I know that faith in Christ has sustained those from whom I am directly descended through nightmares that I can’t even begin to imagine. I believe in the life, death, and resurrection of Jesus. I believe that Jesus is for everyone, everywhere. And yet – the waters are muddied. The purity of the Christian faith, for me, is ruined – even while I still believe. And now that I have found ways to connect with and learn about the ancestors that I have felt watching me all my life – I don’t want to pass up that chance, either.

At the end of that documentary, something inside me felt restless. It felt like I needed to do something about what I’d just seen. I desire to be faithful to Christ, but I also carry a deep inner sense of my ancestral self. And as more and more of my Black contacts and acquaintances make the transition from Christianity to Traditional African Religion – I can’t help but to innately understand why they’ve done so.